"Sh-h-h-h! Boom! Ah! Lou-is-i-an-a!"

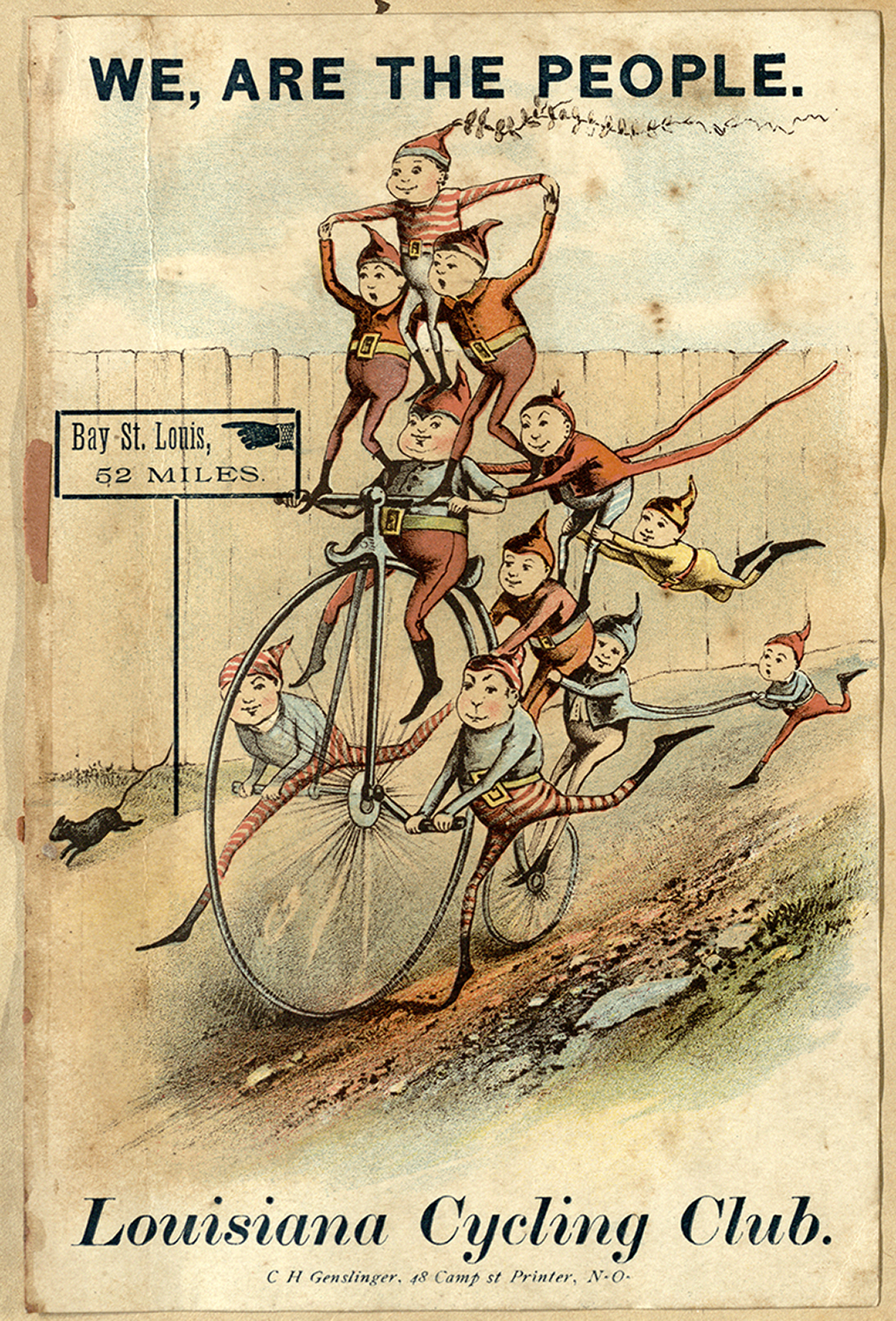

A Short History of The Louisiana Cycling Club

By LACAR MUSGROVE

The Louisiana Cycling Club, formed in New Orleans on July 7, 1887, under the aegis of a young, sharp-witted scribe named Richie Betts. The LCC was the second bicycle club in New Orleans (not counting the short-lived Crescent Wheelmen, which formed earlier that year but lasted only a few weeks). The first, the New Orleans Bicycle Club, was organized in 1881 by a jeweler named A.M. Hill. The LCC was formed by members of the NOBC who split off for reasons that are now unclear but possible to guess. The NOBC operated on formal terms, its rides organized in a stiff military fashion. LCC members were more interested in fun and revelry, throwing parties, coordinating group outings to picnics in the countryside, drinking, and generally enjoying themselves. By the end of the 1880s, the LCC was the dominant club in New Orleans. Members of both clubs were also members of the Louisiana Division of the League of American Wheelmen, and they worked together to hold official League meets at Audubon Park, the first being in September of 1887.

Starting with nine members, the club grew to 33 by its first birthday, and to 90 by its third. At the time the club was formed, all of the members rode penny farthings, although later many members adopted the "safety." The club held regular social rides around the city and made excursions to the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, the farms of Gentilly, and the swamps of St. Bernard. Members held road races along the newly asphalted St. Charles Avenue as well as along the New Basin Canal shell road, now West End Boulevard, and track races at the now extinct horseracing track at Audubon Park. They sponsored railroad excursions to Biloxi and Bay St. Louis, where they held races on the beach.

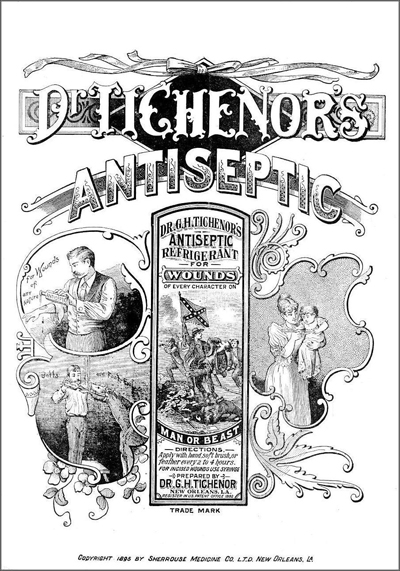

Among the members of the LCC were Dr. Tichenor, of antiseptic fame, and his son Rolla. Dr. Tichenor sponsored cycling races in New Orleans by taking out advertisements in the racing programs and donating bottles of his antiseptic as prizes

In 1890, the LCC built a clubhouse at 1637 Octavia Street that still stands today as a private residence. They were the first cycling club in the South to build their own clubhouse. When the clubhouse opened, the LCC had 78 members and 10 honorary members, including 7 women. The house was complete with a ladies’ parlor, an octagonal-shaped reading room, a billiards room, a banquet hall, a “wheelroom” for storing bicycles, and a janitor’s quarters. The clubhouse was a venue for “smokers,” or men’s parties, as well as “ladies’ socials,” at which members of the club, many of whom were also active in the amateur theatre scene, performed a variety of acts includ-ing singing by the official LCC Quartette, dancing, pantomime, comedy, and acrobatics.

The club was politically active, pushing for improvements in infrastructure and the rights of cyclists to ride on public roads. In 1891, due to the efforts of the LCC, the state legislature passed the Liberty Bill, which gave cyclists the legal right to the use of all public roads.

The club’s founder, Richie Betts, was the official scribe of the LCC. He left New Orleans in 1890 to move to New York, where he became editor of the New York Wheel and later Bicycling World, both major national cycling magazines. That year he wrote of the LCC in The Wheel:

“Down in New Orleans, an interesting little place bordering on the banks of the muddy Mississippi, in the State of Louisiana, there is a bicycle club —the Louisiana Cycling Club by name. It is a pretty lively organization, too. It owns its home, a $500 piano, a $40 hat rack and a quartette, and is withal composed of the jolliest crowd of good fellows it is possible to meet. The house is a cozy little place, the piano is a beauty, the hat rack ditto, but the quartette is quite out of the ordinary run—not as regards beauty, however, but it is the most willing aggregation of song birds (note this) that one will come across in the fourteen States. It has a record of never having been urged to sing twice.”

Betts made his career as a cycling advocate. He also became the first president of the Federation of American Motorcyclists, organized in 1903, and was long the editor of Bicycling World and Motorcycle Review. Betts published editorials on behalf of cyclists’ rights in the New York Times into the 1920s. In 1907, he wrote in the New York Times, “Despite its abuse, the real position and benefits of the bicycle always have been apparent: nothing has arisen to take its place, nor is it conceivable that anything of the sort will arise.”

The LCC operated until 1893, when, due to the failing fortunes of both clubs, they consolidated with the NOBC to form the Pelican Cycling Club, of which there is no record after 1893.

Read more about New Orleans cycling history on the author's blog

Lacar's recent hybrid pamphlet/broadside from NOLA DNA:

Louisiana Cycling Club Spokes Scrapbook, accession 98-62-L, Williams Research Center, The Historic New Orleans Collection

New Orleans DNA: vintage bycycle print block card series: These cards are printed on fine paper with archival inks. Complete Series is comprised of over 15 letterpress prints.

Leave a comment.

comments powered by Disqus