Old Newspapers, New Value

How 30,000 antique New Orleans newspapers listed on Craigslist found a home

By J.S. MAKKOS

One Thursday morning, I found a post in the “free” section of Craigslist for a sizable collection of historic New Orleans newspapers.

Months earlier, the very same collection had been for sale but now it was being given away, so I sent off an email indicating my interest. Not 30 minutes later, I received a phone call from an unknown local number.

The woman on the other end of the line made it clear the situation was time-sensitive and asked if I could meet her that afternoon. I packed my bag and set out for a neighborhood in the shadows of the dilapidated Dixie Beer brewery. I cruised five miles in the crushing heat, and my front bike tire went flat four blocks from the destination. When I finally arrived, the woman was waiting. She led me into an unassuming storefront containing thousands of boxes stacked in three long rows that filled the room from floor to ceiling, each row shrinkwrapped to prevent collapse.

"So, do you think you could have this all out by Sunday?"

Her request overwhelmed me, but I knew I was staring at a treasure, and said I had to make a call, “Can I let you know in an hour?" It just so happened that my studio space was situated above a warehouse, so I dialed my landlord’s number, and persuaded him to let me use the space.

The next day, my landlord and I rented a 17-foot box truck, and found a few friends to take part in a mock fire-bucket brigade. We were topping-off each truckload with as many boxes as could fit. Each parcel contained 15 airtight plastic tubes, an antique New Orleans newspaper sealed in each.

It took us six trips in four days to move 50 years of history five miles across town.

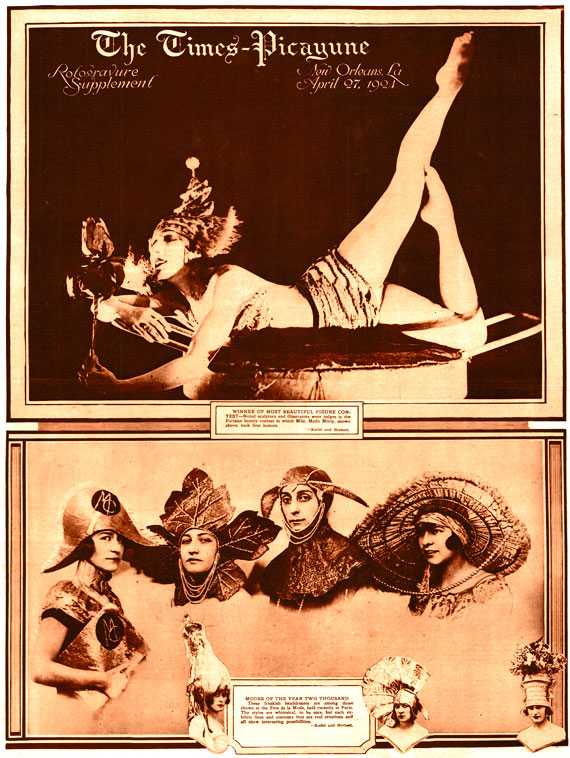

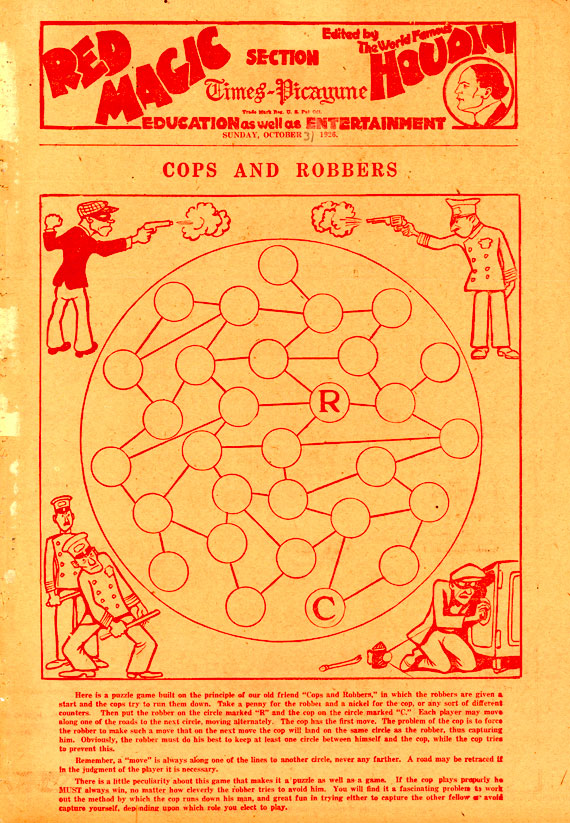

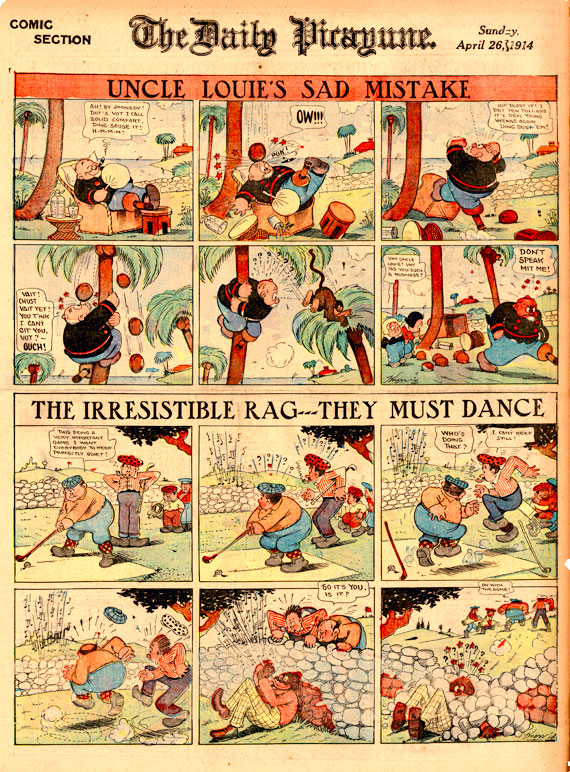

Back at the warehouse, I eagerly began unpacking box after box, moving some of them up the spiral staircase into my studio. As the cardboard was broken down, the tubes piled up. There was no order to the collection whatsoever, but I noticed some thematic patterns and began a crude inventory. I stacked Society sections on the futon, Comics in the bedroom, Sunday Magazines next to the drafting table, sepia-toned Rotogravure photo supplements in the living room, Theatre and Cinema sections near the desk, Literature by the letterpress. Out of necessity, I constructed a wall of tubes using the less exotic looking papers. But there was something spectacular about each one—a gem of information lost in time. It wasn't until several thousand tubes were sorted and stacked that the full flavor of the collection was revealed.

There were papers from the The Daily-Picayune dating back to 1888, some from the The Times-Democrat, and many more from the first decade and a half of The Times-Picayune, which was created by the merger of the Daily-Picayune and the Times-Democrat in 1914. Reading a book on the history of the Picayune, I learned of Eliza Jane Nicholson, the first female proprietor of a major American newspaper. Much of the collection, it turned out, contains her innovative publishing legacy. So I named the archive after her: The Eliza Jane Nicholson Digital Newspaper Archive.

Although there are many books about historical New Orleans, there is a dearth of material about the technological evolution of these newspapers.

Early chromolithography drew me in, so first I delved into the four-color lady's fashion sections and two-color comics. I researched names like Harold Knerr, Grace Drayton, Gene Byrnes, Bud Fisher, Sidney Smith, and countless other comic legends. I discovered "Red Magic" papers from the 1920s, edited by Harry Houdini himself.

I'd fall asleep each night with hundreds of newsprint scrolls, tubes stacked in honeycomb patterns against my bedroom walls. After several months, I noticed the 10-foot-high, 15-foot-wide wall of tubes began to slope more each day. I always figured I had time to fix it, but one night it came crashing down, barricading my bedroom door. The train that travels by the studio and shakes the building was too much for the trapeze act.

It took me half a day to bail it out. I had tubed myself into a corner.

The next question was: what to do with all this precious archival material? I made calls to those I thought could offer advice. I asked archivists, librarians, professors, deans, scholars, appraisers, curators, lawyers, editors, and artists—anybody I thought could help me put value on the archive.

An appraiser told me what I had rescued was worthless. A major auction house offered to advertise and sell it on my behalf. A museum curator told me outright, “newspapers are not art.” The Times-Picayune, struggling to stay afloat, showed complete disinterest. Collectors hounded me for the Mardi-Gras papers. Professors and scholars wanted the pieces that were special to them. Magazine and book editors were interested in republishing excerpts. Archivists explained how the undertaking was daunting. Librarians were always there to help. Artists, mostly, wanted to explore it. Many shared my vision of creating a new digital repository.

The more I researched how to care for and manage such a collection, the more pieces the puzzle had.

At the advice of a former librarian friend, I ordered Double Fold: Libraries and the Assault on Paper and read it over a weekend. Author Nicholson Baker describes the movement by libraries to discard volumes of surplus text, a trend he decries as anti-intellectual. Providing digital access to resources, he argues, should not necessitate the removal of physical archives. Baker specifically mentions bidding on the Picayune collection. The entire newspaper repository had apparently survived a Nazi bombing, only to later be deaccessioned a year later by the British Library. (I sent a letter to his publisher explaining how I secured part of the archive, but have yet to hear back.)

By chance, the copy of his book I acquired online had once been owned by a public library in Texas—a book on deaccessioning itself auspiciously deaccessioned.

As a printmaker, my work is to reintroduce images and stories from the past into people's everyday lives. My best guess is that this obsession comes from watching my dad, a salvager and tinkerer who rebuilt antique lamps in his workshop and restored them to their full dignity. I can't exactly restore old newspapers in the same way, but I can make products that evoke the ethos. Most of the archival collection is in the public domain, which means it's possible to revive old images and text in prints, postcards, books, even T-shirts and beer coasters. The possibilities seem endless.

Of course, setting type is not about novelty; it's about the tactile accessibility of print history, about giving the past a material now. There are other, more immersive ways this kind of history ought to be shared. The city’s tricentennial is approaching. What better revive the grandeur of old New Orleans than by linking antique presses and the content of Victorian-era newspapers to today's state-of-the-art technologies?

Over 40 years ago The Times-Picayune, like many other newspapers, dispensed of their physical collections and condensed them to microfilm. This resulted in a low-quality, difficult-to-search archive. The gray scale of photography disappeared entirely and color was completely lost. But now we can build a new digital archive that is fresh and relevant, stitched into the city's geography and culture, ultimately focused on promoting understanding of and access to its textual mythos. I am developing business plans, writing grants, and building a website to promote the project. More importantly, I am trying to find a home for this archive, a place where I can unpack it and sort it while maintaining my identity as a printmaker whose chief task is to triage the technology of a world gone digital.

I’ve recruited archivists, artists, curators, graphic designers, grant writers, media history experts, and am building a team of volunteers. We're designing prototypes that re-imagine this material for the modern market. Preserving an archive like this is not enough. Today's technologies and analytical tools will allow us to revisit these newspapers and extract more meaning from them than was ever possible when they were first printed.

At a grant writing seminar this past year, a pathologist explained how, by creating a highly-searchable database of content from 50 years of newspapers, we might develop complex formulas to predict the future. That may be a stretch, but an appealing one.

"Anybody can always just stop by, pull a tube out of the wall, ask it a question, and find something pertinent to their struggle," I told him.

Since then, I've been referring to the archive as an oracle.

AUG 28 2014, 8:01 AM ET published in The Atlantic

Leave a comment.

comments powered by Disqus