A Brief History of Bullfighting in New Orleans

A Brief History of Bullfighting in New Orleans

For decades, bullfighting drew blood and protest in the Crescent City

BY J.S. MAKKOS

CHIEF CURATOR, NOLA DNA

WITH JULIEN GORBACH

MASS COMMUNICATION, NICHOLLS STATE UNIVERSITY

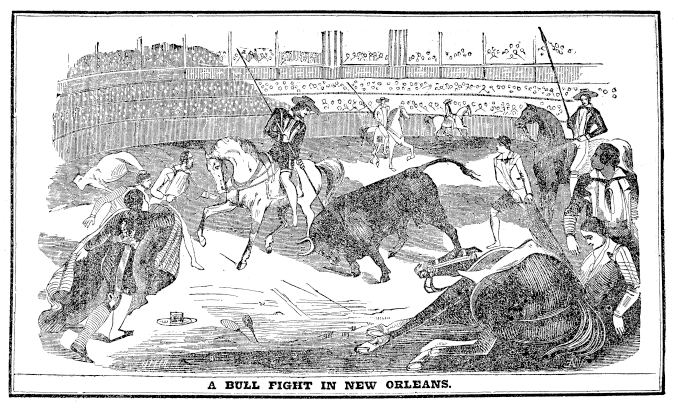

NEW ORLEANS—It’s a little-known fact that matadors once waved their red capes at charging bulls in this city.

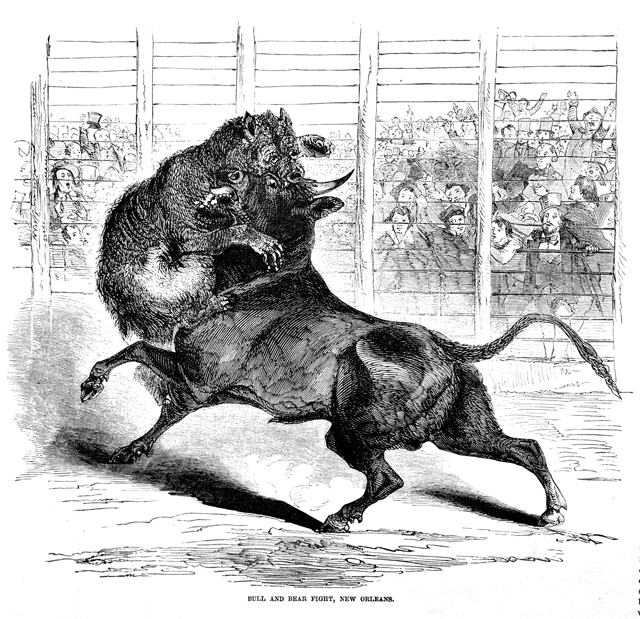

Bullfighting was one of the savage and controversial blood sports that became popular here during the 19th century, along with gruesome battles to the death between tigers and grizzly bears.

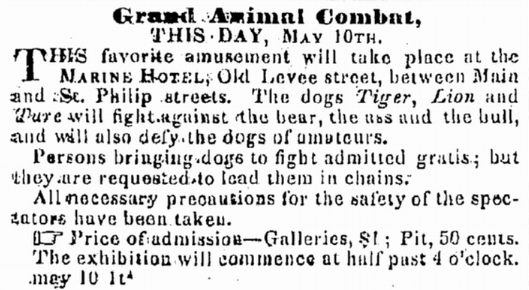

Drawn by advertisements that promised "Grand Animal Combat," thousands flocked to the Marine Hotel at Levee Street, the Arena at Algiers, or Place Publique, later to be known as Congo Square, to see such clashes as between a dozen dogs and a strong and furious Opelousas Bull.

“New Orleanians bet on anything from the earliest days, and sports were huge here—many sports that would have had PETA up in arms for sure,” said Connie Atkinson, an associate professor at the University of New Orleans.

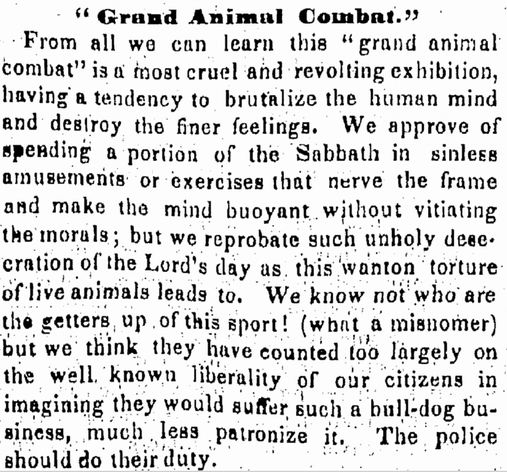

One Daily Picayune account from May 26, 1840 called it “a most cruel and revolting exhibition, having a tendency to brutalize the human mind and destroy their finer feelings.”

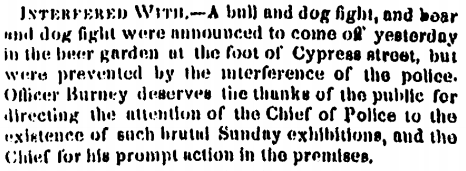

The bloody contests took place on Sundays from at least as early as 1817 to the middle of 1856, when authorities finally responded to the uproar about animal cruelty by shutting the events down.

The bullfights may have started under Spanish rule, between 1763 and 1801.

Pepe Llulla, proprietor of the Arena at Algiers, promoted fights in the authentic style of Spain and Havana, billing Spanish matadors such as Don Guillermo Garcia and Don Francisco Guerra, and striking up the traditional anthems of the bull ring to complete the atmosphere.

"New Orleans was very connected to Mexico and Cuba, and the Spanish world was very close-knit in a lot of ways," said Atkinson.

According to one 19th century guidebook, “New Orleans has a history replete with strange and barbaric sports, brought to Louisiana by the French and Spanish, diversified by the Creoles, and added to by the Americans.”

Bullfighting is also said to have roots in the butcher trade. Baiting a bull before slaughter was done to get the blood flowing, which was supposed to make the meat taste better.

Atkinson added that cockfighting, dogfighting and other such opportunities to wager were typical of any teeming port town.

"If you work on emptying these ships, you get a whole bunch of money, and you're off for a couple of weeks,” she said. “It's like working offshore. You get cash and you have this leisure time for leisure activities, so these things became practical: ‘How do you get money off this guy?’ Well, a card game…"

The bullfights of New Orleans quickly became the stuff of legend. One tall tale, supposedly penned by Davy Crockett, recounts his visit to an arena some time earlier, when he had been on a trip to the half-moon city to “make sale of a few hundred barrels o’ allegator oil.” With “darter” Ann Crockett and a fellow congressman in tow, the king of the wild frontier became so enthusiastic that he finally leapt into the ring, where he vanquished three ferocious beasts with his bare hands.

An etching from Davy Crockett's 1849 Almanack

accompanies his tall tale of a Bull Fight at New Orleans.

(Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society)

The fights in the city became notorious, too. An article in the New York-based Illustrated News from April 23, 1853 recounts a bloody melee that broke out within a mob surrounding a large cage, in which a powerful, slate-colored bull had been pitted against a grizzly. Just as Napoleon Fourth gored Bruin the bear, the people in the crowd began to battle each other with brickbats, clubs, boards and turf for a chance to see.

A depiction that laid bare the graphic nature of animal bloodsports

from the Illustrated News, New York, April 23, 1853.

(Courtesy, New Orleans DNA)

At cockfights in which some 20 combatants were placed in the ring at the same time, handlers would blow a concoction of whiskey and garlic into the nostrils of the birds to revive them for further action.

These were spectacles of cruelty. One of the earliest accounts from 1817 promised that fireworks would be strapped to the victorious beast’s back.

By the turn of the century many of these events were phased out and laws were passed against them in the Louisiana legislature. Revivals were attempted thereafter without success. The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals filed an objection to one effort in 1904.

“Bloody stuff, and some of it endures today, in illicit form,” said Richard Campanella, a professor at Tulane. At a site along Lincoln Beach, Campanella has found dog bones and what appear to be the remains of other fighting victims, although he can’t be sure the animals didn’t die by other means.

"You might want to go out there and see," he said. "Warning: it’s macabre.”

BONUS CONTENT:

BONUS IMAGES:

Illustrations of controversial female bullfighters from Barcelona, coined as"Girl Bull Killers", from the Daily Picayune, March 15, 1896. (Courtesy, New Orleans DNA)

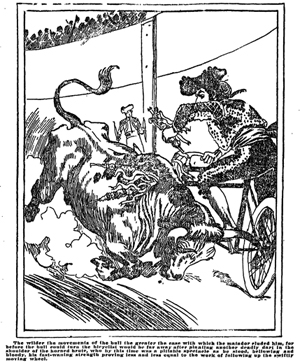

Fighting a bull from a bicycle seat: a merger of the modern and barbaric. "Up-To-Date Bull Fighting", Daily Picayune, December 3, 1899. (Courtesy, New Orleans DNA)

A version of this story was originally published on July 9th, 2014 in the New Orleans Advocate

Leave a comment.

comments powered by Disqus